SINGLE COURSE SHOOTING DOG STAKES

This article comes from the Hunt Collection

and the subject matter is dated no later

than the fifties. Author unknown

GENERAL

For about 75 years sportsmen in the United States and their pointing dogs have been participating in field trials. At first, all conditions were either pointers or setters, game was plentiful, and space was not restricted. Even under these uniform conditions, there soon arose many differences of opinion of the winning dogs. Throughout the years many efforts have been made to standardize the regulations for the pointer-setter-quail trials. Two national organizations, American Field and American Kennel Club have achieved considerable success in this respect, and today all recognized field trials must conform to the minimum standards of one or both of these organizations. These standards were predicated for the most part upon traditional concepts of the pointer-setter-quail trials, and were necessarily broad and general. Even after the publishing of these standards, both handlers and judges have had to rely primarily upon their personal experience and tradition as a yardstick to judge the dog’s performance. This seems to have been done with surprising lack of contention and considerable uniformity in the case of the “classic” field trial.

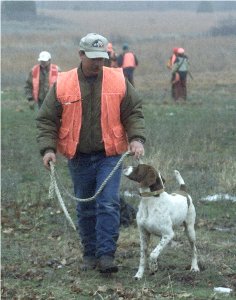

own style, characteristics and capabilities to further complicate the judging standards. In general, these additional breeds appear to have one characteristic in common by which they can be distinguished from All conditions have drastically changed since the beginning of field trials, without a corresponding change in the rules and standards. In addition to the pointers and setters, we now have four other AKC recognized pointing breeds Brittany Spaniel, German Shorthair Pointer, Weimaraner and Wire Haired Pointing Griffon. The Vizsla will soon be added to this list. Each one of these breeds brings to the field trial its the pointer-setters. They are utilized principally as personal hunting companions of handlers on foot who wish them to both point and retrieve game, and in field trials, they are almost always run in “shooting stakes”, where the birds are actually shot and retrieved.

Since the beginning of field trials, the pheasant, grouse, chicken, chukkar and Hungarian partridge have bee added to our list of game birds used in field trials. These birds, with their varying habits and habitats have further complicated the pointer, setter, quail concepts. Then, too, the scarcity of all game birds and the ever decreasing boundaries of areas available for field trials have forced the adoption of the single course trial as a popular substitute for the multiple course field.

Apparently in an attempt to distinguish between the practical shooting dog and the classic field trial dog, the American Kennel Club has established standards for the “gun dog” and the “all-age dog” as follows;

“A gun dog is a cover dog, suitable for gunning on foot. The dog should hunt with and for his handler at all times. He should show or check in front of his handler frequently, never ranging out of sight for a length of time that would detract from his usefulness as a practical gun dog. This should be done preferably with style, intelligence and intensity. He must be under command at all times and quarter his field as directed.”

“An All-Age dog should run a good ground heat and hunt the cover where birds are likely to be found, negotiating the course in such a manner as to wind all the likely spots thoroughly, but nevertheless quickly, adapting his range to the nature of the terrain with optional wider range and more speed than is desirable in a gun dog. The dog should give a finished performance and should be under control at all times. He should, upon locating game, point staunchly and be steady to wing and shot. If birds move, he should relocate and pin them. When the brace mate is on point, he should back, if not on sight, then on command. Intentional flushing, lack of steadiness to shot and flush and failure to handle birds, are more serious faults than are training faults and bad manners.

While these standards are carefully worded and must be accepted, the real distinction is further confused by the fact that the pointers and setters and “all age” trials. Actually a careful perusal of the two sets of standards indicate that the only difference between the “gun dog” and the “all age” dog standards lies in the matter of speed and range, and even as to those the requirement is “optional.”

It appears that the time is long past due when either the American Kennel Club and/or American Field should officially recognize the wide divergence in types of trials, dogs and circumstances, and prescribe a reasonable set of standards for each. There are so many variables involved that it is impossible to establish standards to fit each individual trial or breed of dog, or type of game. It does appear that one type of trial is so far removed from the “classic” concepts as to require a separate set of standards, the Single Course Shooting Stakes. Here we have the following features that are not always common with other trials, foot handlers, restricted area, planted birds, and the retrieve of shot game.

These standards for the single course Shooting Dog involve no new or novel concepts. Each standard of performance has been taken bodily from existing regulations or the written opinions of the leading judges and experts of the classic pointer, setter field trials. Consequently, these standards represent nothing more than an attempt to logically compile the principal time-honored concepts of the ideal pointing dog which apply to this particular type of trial, and publish them with the hopeful purpose of establishing some unanimity of thought among the judges and participants in the Single Course Shooting Dog trials.

These trials are conducted under the rules and regulations of American Kennel Club and/or American Field. Therefore the regulations and standards of the appropriate organization will be strictly followed, and nothing contained herein shall be construed to alter or modify such regulations. Within these limitations, all officials and handlers will be guided by the following standards……

STANDARDS OF PERFORMANCE

FOR SINGLE COURSE SHOOTING DOG STAKES

GENERAL

A field trial is a test of a dog’s hunting, pointing and training characteristics under controlled circumstances designed to simulate actual hunting conditions in the general vicinity of the area where the trial is held. The judges must determine the winners on the basis of observed performance alone. The judges must disregard all prior knowledge of the dogs and their handlers, and no placement should ever be made on the strength of what a dog should, or could have done.

The trial will be divided into two parts, the back course, and the bird field. About 60percent credit for total performance will be for back course work, and 40 percent for the bird field.

BACK COURSE

In a one-course trial the best test of a dog’s intelligence, bird sense, adaptability and willingness to handle is on the back course. He is presumed to be hunting birds in that area, not using it for willful excursions, as a corridor to the birdfield or place for aimlessly strolling with his handler. He should hunt during bird season with his handler, looking for his limit of game. As a practical matter, the limits of the back course and the bird field should be considered as being surrounded by “no trespassing” signs, until the order to enter the bird field has been given by the judge or field marshal. Credit or discredit awarded a dog will be based upon, but not limited to the following standards:

RANGE.

This is one of the most commonly misunderstood features in shooting dog trials. It cannot be defined with mathematical nicety, but must always be resolved in terms of the dog, handler, terrain and cover. First of all, the dog must hunt, and he must hunt areas where the birds are likely to be found. This may be 20 yards, or 500 yards from the handler. An initial “straightline” cast may be excused as a demonstration of the dog’s natural exuberance, but no credit will be accorded such purposeless running.

A shooting dog is expected to “hunt his way out”, testing nearby birdy spots first, and then proceeding to more distant objectives. This will be done with the pace of handler and dog regulated so that the entire back course will be hunted as thoroughly as possible within the allotted 22 minutes. The judges will consider the fact that the gun dog customarily hunts for a handler on foot, and within an area that has well defined restrictions. In this respect lies the principal difference bet5ween single course dog trial, and a multiple course trial where the birds are wild and scattered, the area has no practical limitations, and the handlers are mounted. In these trials sheer speed and “big running” dogs are important factors not necessarily required of the average dog in a single course trial.

PACE.

The pace of a shooting dog will be so regulated that he can adequately test the air scent of as many “birdy” objectives as possible within the allotted time and area. He will not “outrun his nose”, nor will he potter over ground scent nor linger near likely objectives longer than is necessary to detect the presence of birds. The dog properly “testing” the greatest number of birdy spots during his run in the back course will excel in this department.

CASTS.

A “cast” by definition is “purposeful hunting”, not a mere demonstration of speed. Casts need not follow any particular geometric pattern, but should be designed to cover the area in front and to each side of the handler in the most expeditious manner possible. A dog will not be penalized for occasional inside turns nor for “coming from behind” if it appears to the judges that these patterns were caused by a genuine quest for game. Consistent coming from behind will generally indicate lack of control or intelligence.

STYLE.

In this department, the dog’s natural ability is more clearly demonstrated than in any other. The handler who “over-handles”, denies the judge the opportunity of observing the dog’s natural ability. Other factors being substantially equal, the dog that does the job with the least amount of handling will get the nod.

Each breed of pointing dog will hunt in a manner characteristic to that breed. Great care should be exercised in selecting judges who are familiar with the particular style of the breed or breeds he may judge. While “style” is of great importance for many reasons, much care must be used by the judges not to confuse “style” with “form, for, in the final analysis, true style is no more or less than the demonstration of the desire and ability to hunt well. In other words, the dog that is hunting, no matter what his form, is to be preferred over the dog that is simply running, even though it be with perfect coordination and grace of movement.

A point with unsteady tail is better than inability to find a bird. A tracking dog will find more game than a line-runner, and any form of honest to God search for birds will produce more than mechanical quartering. Fortunately, the same inherent qualities in a dog that causes him to produce, almost invariably constitute the “style” for which the judge is looking, and it is indeed the rare case where the demonstrated abilities of two dogs are so similar that form alone will decide the winner.

COURAGE.

A gun dog is expected to hunt independently, and rely upon his own ability to find birds. Consistent trailing of a bracemate will be grounds for non-placement. Within practical limitations the dog should drive toward his objectives as directly as possible. Consistent following of roads, paths or easy terrain may indicate lack of courage. Courage proceeds maximum physical effort when the dog is tires, sick or injured. This quality alone will frequently be the difference between an excellent dog and a champion, and should be given considerable weight by the judges.

INTELLIGENCE.

Intelligent hunting consists of primarily of selecting the places where birds are likely to be found, and examining them sufficiently well to insure that they are, or are not presently there. The gun dog must perform this mission on his own initiative, both accurately and quickly, taking full advantage of the wind and air currents in checking his objectives. He will quickly diagnose foot scent, ground scent and old scent, and leave them in quest of the live body scent he is seeking. He will avoid repetitious search of the same area, and will give the general appearance of knowing exactly what he is doing.

CONTROL.

AKC Standards require the gun dog to hunt ”with and for his handler at all times”. This result is a combination of the dog’s natural instincts and his training. AKC further requires that the gun dog “must be under command at all times and quarter his field as directed”. Any dog not under the control of his handler, no matter what his other qualities, is quite useless for any practical purposes and should never be placed in a field trial.

The judge should require each handler to demonstrate control to his satisfaction. Before the start of each brace, the handlers should be told just what the judge expects of them in this respect. Lack of control can well be cause for non-placement of a dog. On the other hand, any control by the handler over a phase of conduct that the dog should perform by instinct or prior training, prevents the judge from determining the dog’s true ability. For example, the dog that gets out only to the tune of his handler’s whistle, may simply be getting his exercise.

The judge that sees a dog turn only upon command may well decide that the dog has no independent hunting ability. A dog that has been “whoaed” into a point demonstrates absolutely no pointing ability, and the handler that keeps his dog in place during flush and shot by constant commands, signals or other means of intimidation, must be outranked by the dog that is steady without any assistance from his handler. The dog that voluntarily backs or honors his bracemate’s point has demonstrated the true courtesy and sportsmanship the distinguishes him from the “meat hound”, whereas the dog that stops only upon command has shown the judge nothing but basic obedience.

No credit whatsoever should be accorded by the judge to a phase of the dog’s performance which he has been precluded from observing by over-handling.

ENDURANCE. Any gun dog under acceptable weather conditions should be able to negotiate 30 minutes of ordinary back course and bird field with no noticeable slackening of pace. Failure to do this generally indicates a serious limit ratio of the dog or his training.

Stop to Flush. A stop to flush must always be recorded in the dog’s favor. When working in heavy cover or not under constant observation, it is generally possible that the dog which, when first observed, has stopped to flush, might have been on point at the time of flush. Where reasonable doubt exists, it should be resolved in the dog’s favor and full credit for stop to flush should be given. Even when the dog must be penalized for a deliberate flushing, or an accidental bumping, his subsequent manners in stopping to flush must be rewarded.

FAILURE TO STOP TO FLUSH.

(a) If this failure is followed by a deliberate and substantial chase, the dog should generally be eliminated as a contestant. (b) If this failure was simply the inertia of following a running bird, and is immediately controlled, little discredit should be involved. (c) If the dog continues his original cast without more than a casual look at the bird, it should be assumed that he was so intent on his objective that he was not consciously aware of the flushing bird; in which case, no penalty is involved.

POTTERING.

Dogs that linger over ground scent, sneak from bush to bush at an unnaturally slow pace, should never be placed except as a last resort.

ROADING AND TRACKING.

These terms are frequently misunderstood. Tracking occurs when the dog follows the old ground scent of a bird that had previously been in the area. This is generally done with head down and a slow, methodical pace. This is always a form of pottering and is to the dog’s discredit. On the other hand, “roading” occurs when the dog is following the fresh air scent left by a running bird, head high, at great speed and with merry tail.

Roading frequently occurs when the dog is required to relocate and represents a very natural and productive method of finding the bird. Credit should always be given for roading. However, this means of finding a bird is always accompanied by the danger that the game will be intentionally or accidentally flushed, for which flushing discredit must be given. A few rare dogs will pick up the air scent of a running bird and circle it down wind in an effort to pin the escaping quarry and establish a point. When this occurs, credit for exceptional intelligence should be given. This situation arises frequently where pheasants are being used, and requires careful evaluation on the judge’s part to determine exactly what the dog is doing.

OUT OF JUDGMENT.

In a single course shooting stake trial, a dog that is out of judgment for any substantial period, except when on point, should be penalized severely. AKC rules require his non-placement if he is out of judgment for a continuous period of five minutes, except for “outside factors which interfered with his running.” No trial should be run in cover so heavy that both the handler and the judge do not have a fair opportunity to observe the dog most of the time.

Entering the bird field ahead of schedule. A shooting dog must be under the control of his handler. AKC regulations preclude any dog from having “more than eight minutes in the bird field in any stake.” Therefore, any dog entering the bird field before he has been authorized to do so by the judge or field marshal is out of judgment. Under no circumstances shall be given credit for any work performed during this time. If observed, the judge may require that he be called in and handled until the signal to enter the bird field is given.

HANDLERS FOR WALKING OR HORSEBACK.

Shooting Dog Stakes are for dogs customarily handled on foot. Their range and pace should be adapted for comfortable walking. Handlers are permitted to ride only as a personal convenience to them. Where there are foot handlers and mounted handlers in the same stake, the judges and field marshal will insure that the mounted handler has no unfair advantage over the foot handler. The mounted handler will adapt his pace to that of the foot handler. The mounted handler who wishes to leave the field trial party for any reason must dismount, turn his horse over to the marshal or horseboy, and walk to his objective. Birds will not be flushed from horseback. All dogs will be handled on foot in the bird field.

SCOUTING.

The primary purpose of a scout is to make certain that a dog is not lost on point. In Single Course Shooting Dog Stakes, his services should not be necessary. Under unusual circumstances, the judge may send a person of his own selection out to locate a dog. Under no circumstances will any person other than the handler attempt to control or influence the dog’s performance. The judges may, as a matter of courtesy, report a dog’s location to the handler, but unofficial scouting or locating by members of the gallery should not be permitted.

BIRDFIELD

While performance in the back course is much more indicative of a dog’s natural ability and training, it is most essential that the dog demonstrate his ability to find and handle birds. In a single course trial, the bird field generally offers the only opportunity for this. In view of the fact that conditions in the bird field are artificial, great care should be exercised by the judges to insure that credit is awarded for earned performance. For example, little or no credit should be given to the dog who is aimlessly hacking the bird field and stumbles upon one or more planted birds. A dog that is obviously tracking the bird planter to hidden game demonstrates nothing of value to the judge. Equally useless is the dog that refuses to point until he sight points over the planted bird, even though he has had the opportunity to point body scent. Insofar as possible, the style of performance in the bird field should be the same as that expected of the dog working wild birds in the field.

PLANTING THE BIRDS.

Under the most carefully supervised conditions, a planted bird is a poor substitute for wild game. Many intelligent dogs will not point with normal intensity and style a bird on which man scent is apparent. Great care must be exercised by the bird spotters before and during planting to avoid contaminating the bird’s natural scent. Birds should be handled as little as possible, and should be placed as far apart as practicable, near a likely objective. Spotters should never (1) handle birds without gloves (2) hold birds in their arms or carry them against their bodies (3) plant successive birds in or near the same spot (4) twist or tie stems of grass around the birds’ legs or otherwise impede their ability to run or fly.

MULTIPLE FINDS.

The purpose of a field trial is to test the ability of the dog to find and handle birds. Therefore, all other factors being equal, the dog having the greatest number of earned finds, properly handled, will be placed over his competitor. The handler who, having successfully handled one find, holds or restricts his dog, or otherwise discourages him from making additional finds, clearly demonstrates a lack of confidence in his dog. This factor will be considered by the judges in making their placements.

OVERBIRDINESS IN BIRD FIELD.

The shooting dog is expected to hunt the bird field in a natural manner. Dogs that linger over ground scent or sneak from bush to bush, or hunt the bird field in any other than a natural manner will be considered as “pottering”, and will not be placed except as a last resort. The ground scent left by previously planted or shot birds will necessarily be investigated by the intelligent dog, but he should not linger over this scent.

POINTS.

Points should always be made on air scent, except when conditions make that impossible. The point represents the completion of a mission, and constitutes much of the sheer artistry and beauty of the field trial. Therefore, much has been written and painted depicting the “style” of the pointing dog. In this department great care should be exercised not to elevate form over substance, particularly where the bird has been planted and may carry a substantial amount of man scent or other foreign odors. Loftiness is a desirable characteristic of a dog on point, but intensity is far more important than the exact position of the head or the tail. Intensity may be properly demonstrated in many ways, depending upon the wind, the bird, the dog, and the surrounding circumstances. The point must always be the work of the dog, not the handler. A dog that has been “whoaed” into a point has demonstrated only response to command.

STAUNCHNESS OF POINT.

Is a characteristic that should be fully developed long before the trail, and should require few, if any signals, commands or threats by the handler to insure compliance during the trial.

STEADY TO FLUSH AND SHOT.

While a handler may use whatever commands he deems necessary to insure steadiness, the dog that is already without any handling has clearly demonstrated his own proficiency in this department, and he will be given proper credit by the judges. On the other hand, the judge should properly assume that each action on the part of the handler designed to encourage steadiness indicates some lack of steadiness. AKC rules provide that “any use of the hands on a dog, or the use of training aids to hold or restrain a dog fronm breaking or flushing will be cause for non-placement of the dog. The use of flushing whips has been greatly abused and should be discouraged. If it is evident to the judge that the dog is being deliberately intimidated by the use of the flushing whip, or other device, the dog should be severely penalized or disqualified. During and after the flush, the handler should not place his body in such a position as to interfere with the dog’s free choice of movement. As one eminent judge has said, “You can’t kill a bird while reaching for a dog.” It would therefore appear that the proper position for the handler during the flush and kill is that which he would generally assume if he, himself, were shooting the bird. While any substantial movement during flush and kill is evidence of unsteadiness, a shooting dog. In order to properly retrieve, must be trained to mark the fall of the bird. So long as he voluntarily remains in the same place, such movement of the head or body as may be necessary to observe and mark the bird is considered to be finished and intelligent performance, and not unsteadiness. A flushed bird should always be shot while within reasonable range, and there should always be a distinct pause of several seconds after the bird is grounded before the retrieve is ordered by the handler. No bird will be shot except over a point.

RETRIEVE.

In shooting dog stakes, the retrieve is an important phase of the trial. Upon command, the retrieve must be made quickly and tenderly to hand. Whether the dog sits or stands when delivering the bird is optional.

HARD MOUTHING.

Any hard mouthing will be penalized and serious hard mouthing will be grounds for disqualification. When hard mouthing is suspected, the judge will examine the bird. Serious hard mouthing occurs when the dog has clearly departed from his assigned mission of retrieving the game and has intentionally destroyed, damaged or mutilated the game. Evidence of this is most typically shows by a crushed or torn carcass, or other evidence of excessive chewing not an incidental to the retrieve. Proper allowance should be made for the retrieve of live and struggling birds, or birds that have been pulled through brush or other obstacles. However, the dog bent upon mutilating his game wil almost always interrupt the retrieve to accomplish this. IT is rare when serious hard mouthing occurs during a prompt and efficient retrieve.

BLINKING.

Blinking or deliberately leaving birds that he has found is one of the worst habits that a dog can have and, if proven, should be grounds for disqualification. If a dog should flash point a running bird and circle around him for the obvious purpose of re-establishing the point, this should be considered by the judge as a display of more than ordinary intelligence, and graded accordingly. However, a dog that has steadied on point should stay there until ordered on by his handler.

UNPRODUCTIVE POINT.

In shooting dog stakes, the handler is presumed to know his dog and should not call point until the dog has steadied. While the staunch point is supposed to represent the present, physical location of game, occasionally no birds can be produced. When this occurs under such circumstances as to make it impossible to determine whether the point was a valid one, and the birds have

departed unobserved, or was false from the beginning, the dog should be given the benefit of the doubt and neither credit nor discredit awarded. Two or more instances of unproductive points will strongly indicate a pattern of behavior to the judges.

@@@@@@@@@@

This article was written no later than the late fifties & by unknown author & comes from the Hunt Collection. I have tried to research the article's origination by other sources & been left with no solid information for anyone, let alone a specific anyone. It is possible that Charles Hunt wrote it because until the late fifties (so far) I have found no other Vizsla person, other than Paul Sabo who wrote about field trialing under the FDSB registry. But Hunt was sick most of the late fifties & his other articles are never this long. Even Sabo doesn't usually write this long BUT if the subject warranted Sabo usually expounded. The third possibility is it was written by Fred Schulze who was the first professional handler in the breed. (I think) :>)

If you can identify the author and/or date...

This website composes the private and public collections & lifetime investments of Vizslak peoples around the world with an initial focus on the USA & the field because that is the information SITmUP has processed....so far. Please "respect" our collective work on thevizslaksentinel.com and do not use in an unexpected way. The individual collections form the cornerstones of every Vizsla living and owned by "you" today.

If respected by the readers, the information on this website will remain & grow.

Credit should be given by providing the appropriate Sentinel URL

when quotes or articles are republished.

"The Vizslak Sentinel " (c) Jan 13, 2009

Product of Stuck In The mud Underground Publishing (SITmUP)